STENCIL.ONE

Screenwriting: Character Want & Need

In this tutorial we’ll look at the differences between character want and need and we’ll look at how to design characters with wants and needs that will grab the attention of your audience.

![]() Software version 1.1.1

Software version 1.1.1

Character Want & Need Are Not the Same Thing

Specifically in today’s tutorial we’re going to look at the difference between character want and character need. So let’s jump in.

Character Want

So first, your characters have to have a want. Your character’s want is the fuel that propels your story forward. If your character doesn’t have something they are questing towards then the story will stand still.

Wants drive us to act. And our acts define us as characters.

There is an incredible book, which is a nonfiction novel, called “The Lost City of Z”, which was recently turned into a movie. In this story, our protagonist, Percy Fawcett, was an explorer who formulated, partially through some mystic methods, some ideas about the existence of a lost city in the middle of the Amazon. Unfortunately, his quest towards this lost city, ultimately cost him his life.

The character had such a strong want, that he made the ultimate sacrifice for it.

The click embedded above does a great job of communicating what we need to do as storytellers. The quote, “a man’s reach should exceed his grasp” is taken from a Robert Browning poem, and as storytellers, this quote is something we need to use as inspiration when writing our first scenes. Just get something down that allows your protagonist to grasp at something, but be sure to place that “thing” just outside of their reach.

This is essential to storytelling, because when you’re creating your scenes, these scenes can’t be filled with inaction and your character shouldn’t aimlessly wander around. These scenes need to have momentum and direction, propelling your protagonist into an unknown future. As a sidenote, if you get stuck on these narrative elements, you can always use a tool like Stencil’s prewriting worksheet to help you work through your writers block on these narrative elements.

Therefore, “want” not only serves your character and your audience’s relationship to that character, but “want” also serves your story.

In the lost city of Z, the goal is very simple: To find the lost city of Z. Which is a place that most believe does not exist. After that goal is established, all of the film’s scenes will hang off that initial goal.

Now, you can write this down on paper if you want, but you have to organize these details somewhere. I’m going to use this character profile template which you can follow along with by signing up for Stencil.

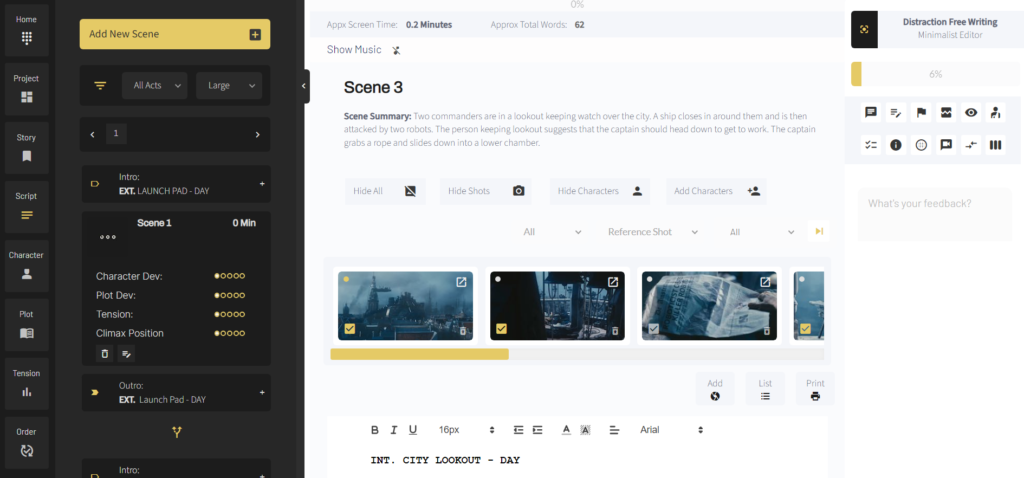

Once you’re logged in to Stencil, you simply need to add a project, then click over on “character” in the sidebar.

From there, you can add a character, and then once the character is added, you can simply “click on this edit button” and the character development worksheet will appear like this:

In my story here, I’ve plotted the Lost City of Z as an example on my plot visualization page. However, in order to make this story come to life, I need character.

For example, in the clip at the top of this post, you’ll remember that in one scene the protagonist needed to make their way through the jungle.

That scene couldn’t exist if we didn’t have our initial goal. Because you can’t make your way through the amazon rainforest, if you didn’t have the goal to get there in the first place.

Or what about the other scene from that clip, when our protagonist was in the jungle and being attacked by a local tribe. That scene also wouldn’t exist without the goal of being there in the first place.

So in Stencil here, I’m going to write that my external goal is to “find the lost city of z”.

Character Need

Keep in mind that goals by themselves can feel a bit shallow and two dimensional if used alone. In order to round out our characters, we need to understand their innermost needs.

Now, keep in mind that the characters themselves don’t always need to understand their needs (at the conscious level at least). Our deepest needs often live below the surface of our consciousness and are therefore, frequently hidden from us. However, as writers we need to know our character’s needs, at least to some degree.

So our character “wants” to go on an expedition to the Amazon. But we need to ask ourselves… why?

And this is where things get really interesting. Because sometimes want and need are aligned, however, more often than not, there is a bit of friction there, and sometimes want and need are even at polar opposite ends of the spectrum.

I’ll explore the importance of playing with the dynamic between want and need in a few minutes, but for now, let’s just focus on identifying the need.

In the lost city of Z, Fawcett knows that he’s seen, at least to some degree by those in the scientific community, as a bit of an amateur. He’s enthusiastic, but lacks a big discovery. Professionally he’s a bit of an outsider. Other explorers are given way more funding, have more resources and bigger teams. Fawcett is a bit of an underdog. Not only because he lacks resources, but his methods are also unconventional and border on, if not dive deep into the worlds of mysticism. And academics and scientists, turn their nose up at him because of this.

So he feels this need to be respected and accepted in the scientific community, and he’s willing to throw a lot of things, including relationships under the bus, to make that happen.

In fact, I think even at a more general level, he has a need to feel proud. His ability to take risks are admired by a lot of people, but he comes up empty handed most of the time. So although he can’t be criticized for not trying, his actual contributions have been very little – and this burdens him greatly. He wants to have his work be worth something. But he feels shame and judgment, where he wants to feel pride and glory.

So he needs this respect, recognition and a stronger sense of pride.

The discovery of something new (which is his “want”), is really just an attempt to try to scratch this itch and gain respect and recognition (which is his “need”).

Now our character has a want – which is to find the lost city of Z. And they also have a need – which is to earn the respect and acceptance of the scientific community and his peer group and family at large.

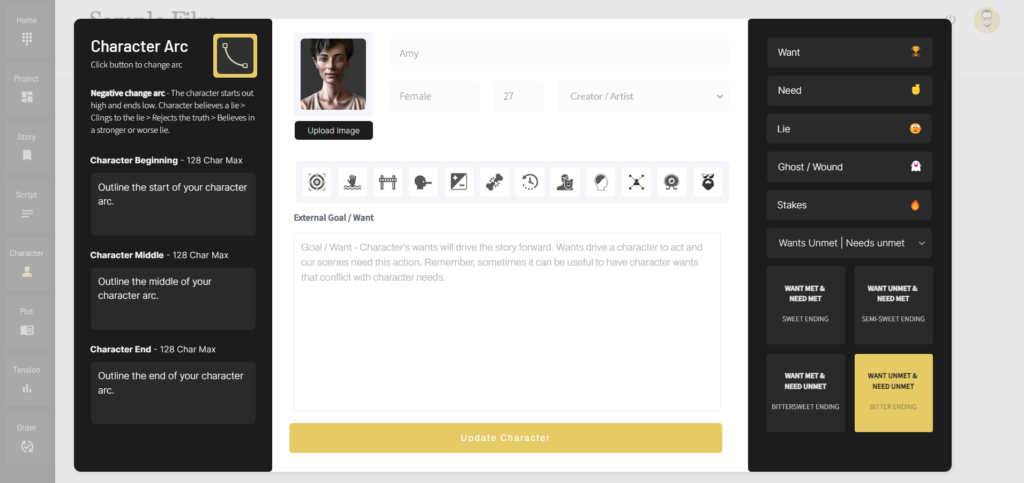

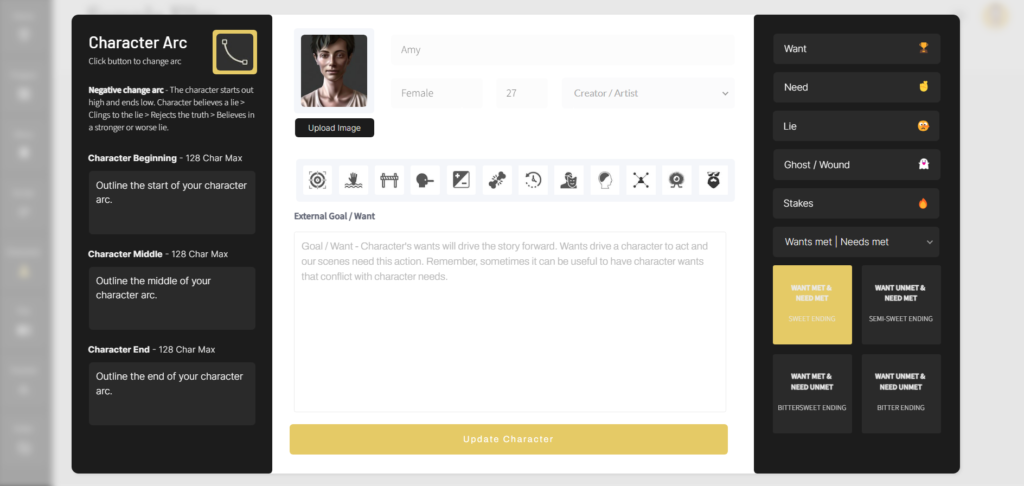

So over in Stencil, I’ll type this all into my character worksheet.

Now, visually you need to see these two fields as layers (see the upper right corner of the image above). Appropriately, one input field is on top and visible, which the audience will see and interact with. The other layer is under, and generally invisible, especially at the beginnings of stories. The layer that represents need is often something that’s more felt than seen. This is true both for the characters as well as for the audience.

What I want to talk about now, is how we, as writers, can create tension between these two layers. It’s often the tension between these two layers that eventually makes the theme of a film apparent. It’s the main takeaway. The idea that the creator of the film wanted you to wrestle with in your mind. Often, it’s the idea that they were wrestling with as they wrote the film.

But we’ll talk about theme in another tutorial. Let’s stay on track. So here, we have these two layers and they don’t always play nicely together.

Let me give you an example from a film cited in the book The Art of Character. This example is taken from a movie called Frozen River.

Essentially, a mother promises her sons a new trailer. That’s the goal (this is what will propel the story from “A” to “Z”). This outward goal is what the audience will see. They will watch the mom trying to save up in order to buy this trailer. All of the obstacles she’ll overcome she’ll need to do so in order to obtain this ultimate want.

But her needs are different. Her need is to “keep her family together”. She just thinks the trailer is the best way to keep them together. But the problem is that her need is elusive to her. She can’t really see it, or if she can see it, she miscalculates how to reach it, and that’s why she puts the target of the trailer in her mind.

And remember, we’re putting things just outside the reach of our main characters so they can’t easily grasp it. Everything can be designed to scale. Finding a lost world in the middle of the Amazon is a huge “want”, but wants don’t need to be huge to be engaging. Your want could be to buy a trailer for your kids. That’s an enormous life goal for someone with very little resources.

No matter what you pick as your goal, obstacles will be introduced that will feel big because of where the character is starting from. In Frozen River, the first obstacle the mother faces as she quests towards this goal is the realization that she doesn’t have the money to buy the trailer.

In order to solve this problem, she gets sucked into some seemingly low risk illegal activities to come up with the money. But this leads her down a disastrous path of immigrant smuggling and she ends up losing everything. Essentially, at the end, her “want”, which was the trailer, was the very thing which stopped her from achieving her “need”, which was to keep her family together.

And that’s one way to create friction between these two layers.

And the same is true in the lost city of Z. Percy Fawcett sets his eyes on a target – an undiscovered world. A place most people don’t believe exists. He begins his journey towards his want, in an attempt to satisfy deeper needs (that not even he is consciously aware of). But his choice of target resulted in him never coming out of the jungle. Dead or alive. To this day, his body has still never been found.

Plot Your Character’s Want & Need Ending

Once you figure out the wants and needs of a character, you can start to plot things out to make your life as a writer easier. You can create a quadrant to determine the final position of this character. Again, this isn’t 100% necessary, but it helps dramatically if you’re the type of writer who gets lost with direction and would rather map some of these milestones out beforehand. There are 4 main types of endings when we consider character wants and needs.

Happy Ending

Happy endings are when characters achieve both their needs and wants.

In the lost city of Z, a happy ending would be Percy Fawcett coming back alive, having found the lost city and earning the respect of the scientific community, his friends and family. In this story though… this didn’t happen.

Unresolved Ending

Next, we have an unresolved ending.

In fact, in Stencil’s quadrant breakdown, we have two. But let’s look at the first. In this quadrant, our character achieves their need, but not their want. Again, in the Lost City of Z, this would have happened, if Percy Fawcett came back alive, without finding the lost city, but maybe he found something else, not his main target, but something deserving of respect. This is kind of a “semi-happy” ending.

Another unresolved ending is where we have the character achieve their want, but not their need.

Again, in our case, imagine Percy Fawcett returned home alive and he found the lost city. However, imagine that his discovery was largely ignored by the scientific community. In this case, he would find himself still without acceptance or respect. This would be a “bittersweet ending”. This is where your protagonist gets what they want, but don’t feel overjoyed by their success because their need wasn’t met. Frequently in stories, this is where the protagonist, for the first time, and often in a cathartic manner, unearths and wrestles with their hidden inner need.

Unhappy Ending

And lastly, we have the infamous “unhappy ending”. This is a tragic ending, where the character neither accomplishes their want nor their need. And in the story, The Lost City of Z, this is what we have. Percy Fawcett never came out of the jungle, never accomplishing either his want or his need.

Conclusion

In Stencil, you can see we’ve only just scratched the surface here. There is so much more that goes into character, so don’t forget to check out the other content over on our filmmaking blog so that you can continue on this journey to learn how to create great characters for your stories.

That’s all I have for you today. I hope you’ve found this helpful!

All-In-One Film Production Software

Stencil comes will all of the tools you need to manage your film production studio. We help you manage storytelling, budgeting, casting, location scouting, storyboarding and so much more!

![]() Software version 1.1.1

Software version 1.1.1

A software solution designed to help filmmakers complete compelling stories.

![]() Version 1.1.1

Version 1.1.1

USE CASES

Feature Films

Documentaries

Shorts

Music Videos

Commericals

Fashion Films